In previous compost conversations we have looked at the importance of carbon/nitrogen ratios, getting the moisture levels of our compost right and getting the density of our piles (bins or bays) in that sweet spot between too heavy and too light.

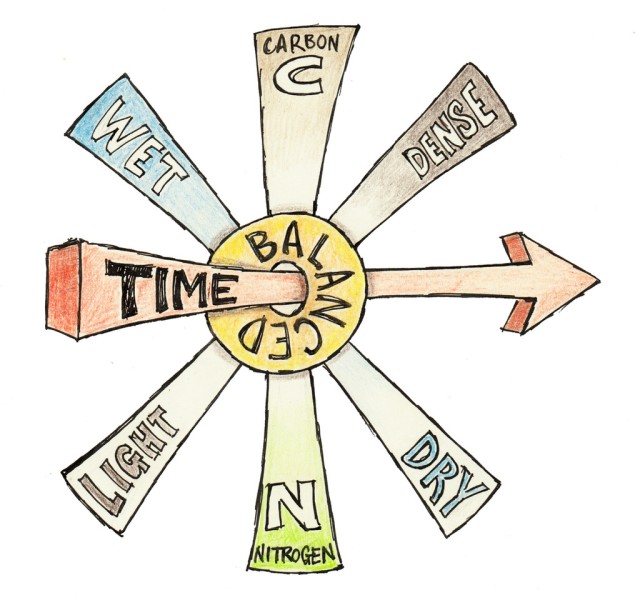

Training our YIMBY composters in our ‘continuous hot composting process’ we use the above illustration of these ‘three axes’ (plural of axis) to show the most important variations we need to get in balance to make great compost.

‘Time’ is the fourth variation in the decomposition process, as every compost pile, or ingredient that goes into a compost, will change along these axes over time.

We use this tool to help composters make wonderfully balanced compost, but it’s also helpful to think about what happens when our compost is out of balance. Let’s have a look at some of those scenarios now.

Too Nitrogen-Rich. When composts are too nitrogen-rich, lacking enough carbon-rich material, the excess nitrogen in the pile will create stinky and/or harmful gasses like ammonia, methane and nitrous oxide, losing nutrients to the atmosphere. High-nitrogen composts tend to be too heavy and too wet, but not always.

Too Carbon-Rich. Overly carbon-rich composts (such as mulch piles) will, in time, break down into useful mulch or ‘mould’, but will lack the nitrogen levels to be a rich fertiliser for leafy garden growth. Carbon-rich composts will tend to be too dry (see below) and too light, and are prone to getting very hot quickly, but then dropping temperature just as rapidly.

Too Wet. Composts with moisture content over 60 per cent will lack the pore-space for enough oxygen so will tend to get anaerobic and stinky. Wet piles are also heavy piles and have similar problems (see below).

Too Dry. The microbes that do the decomposition in compost live on thin films of moisture in and between the compost ‘ingredients’. When conditions are too dry, the microbes will either die or go dormant. So, after a short burst of very hot microbial activity (an extreme version being ‘spontaneous combustion’ in a hay shed) the existing moisture in the pile will be used up and the dry pile’s decomposition will slow or stall.

Too Heavy. Very dense compost piles don’t have enough room for oxygen to get into the pile and for carbon dioxide to leave. They tend to become anaerobic, smelly, and are very hard to turn.

Too Light. Light, airy composts lack good connection between the ingredients, slowing decomposition. Light piles struggle to reach the ideal moisture level of 55 per cent, and the air gaps make for great insulation, creating brief spikes in temperature, similar to the ‘too dry’ pile.

All composts benefit when the blend of ingredients we add to our piles finds balance in the sweet spot of these three axes.

– Joel Meadows works with *Yes In My Back Yard, (YIMBY), a community-scale composting initiative in Castlemaine and surrounds. Send questions or comments to hello@yimbycompost.com, or to book in for a compost workshop.